The Career Narrative

19 August 2020

When we come across new information, we try to piece it together in a way that makes sense. This is a narrative, “a spoken or written account of connected events; a story.” We are most familiar with the narratives presented in novels or Netflix shows. We are less familiar with the narratives present in our careers.

In our careers, there are numerous situations where we are expected to deliver a compelling narrative of a situation we had a part in. Sometimes, we aren’t even aware of what’s expected of us. Other times, we unknowingly sabotage our narratives in activities like resume writing, interviewing, or career planning.

Comparative Narrative

Resume writing can be a source of angst because it forces us to justify how worthy we are as professionals. This process involves coming up with the “major achievements” of our past experiences.

A problem with writing about “major achievements” is that by nature, most day-to-day tasks are mundane. A software engineer spends hours figuring out why a button is green instead of blue. A digital marketer spends hours perfectly aligning text in a Powerpoint presentation. In actually doing the work, we have broken down the overall experience into a collection of small tasks that don’t seem that exciting. How can our experiences coloring buttons possibly compare to those of the “real deal” people in our fields, seemingly changing the world every day?

There’s two scenarios:

- The “real deal” person’s background and experiences are strictly more impactful than ours. Directly comparing ourselve’s to others is a rat race, and we’ll always find a faster rat. The best thing to do here is direct our efforts more thoughtfully in the future towards work we find personally meaningful.

- Their work is just as pedestrian as ours, but they communicated it in a compelling manner. Stephen Covey of The Speed of Trust fame states that “we judge ourselves based on our intentions and others by their actions.” My corollary is “We judge ourselves based on how we experience our work, and others by how we perceive their work.” It’s easy to consume others’ compelling narratives while getting lost in the weeds of our own work.

Most times it’s the latter, or some combination of both. The important thing to note is that our previous work experiences do have potential to be compelling narratives; we just need to shape it.

Presentation of Self

The past is a series of events that has already happened, and is unchangeable. However, the presentation of the past can continually be reformed towards new goals. Though we may not have been thinking about our overall narrative while living our past experiences, we’ll need to work with what we have and form a compelling narrative from the collection of experiences.

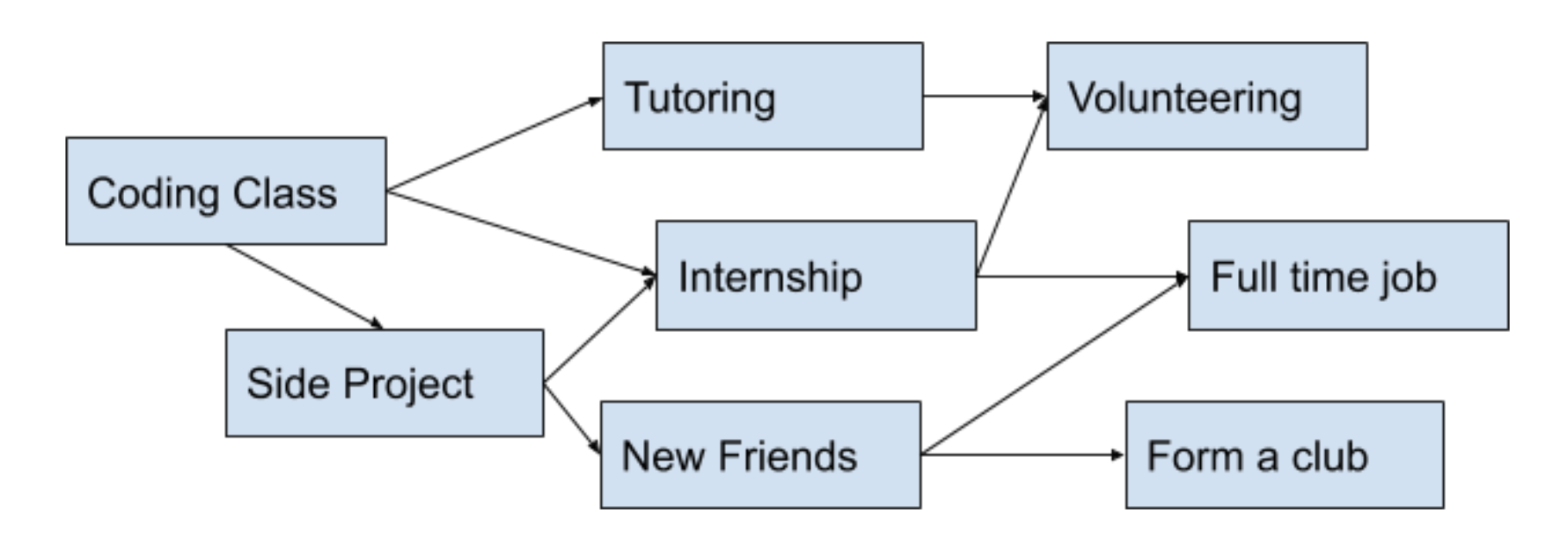

Life is complex, and we’re pulled in many distracting (or exploratory) directions along the way. It looks something like this:

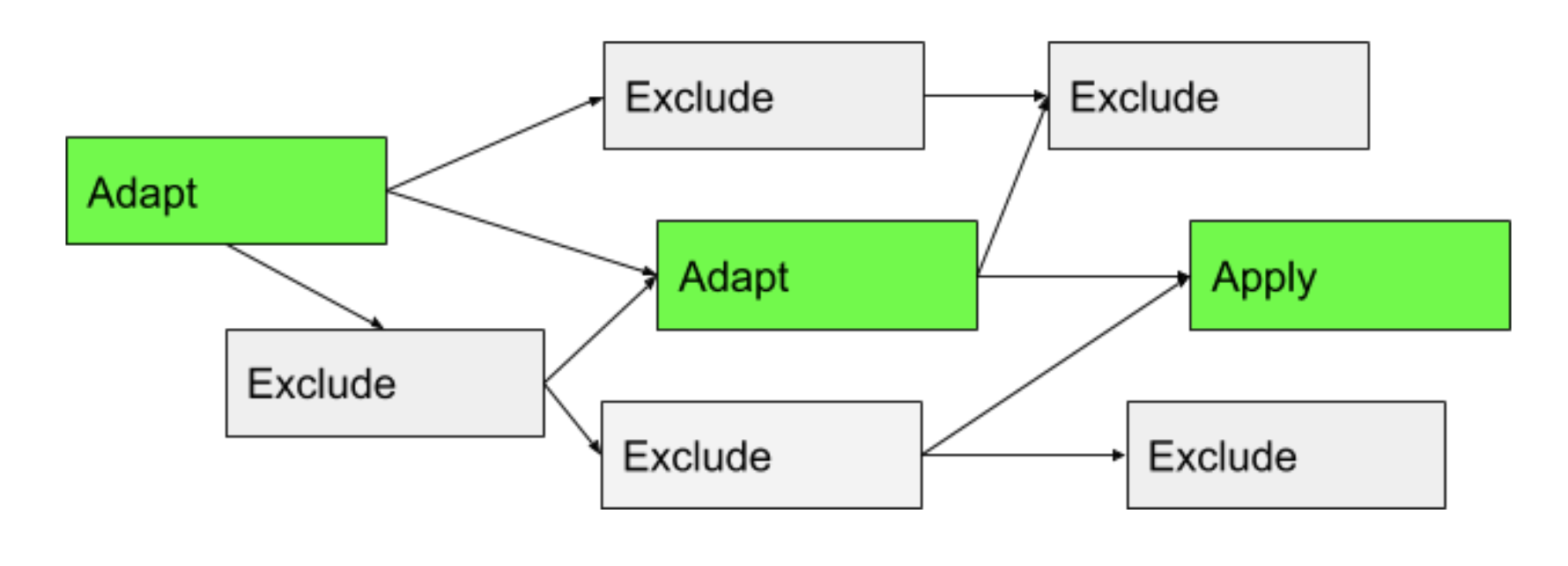

In interviews, the interviewee’s job is delivering a narrative that everything in their life has been led up to this moment of being the most uniquely qualified candidate for the job. There’s two strategies for achieving this goal:

Adaptation. The data point needs to be adapted to fit the attempted narrative. For example, back in college I wanted to be a software engineer (attempted narrative). My first engineering job after freshman year was an internship in test engineering at an automotive battery supplier. My responsibilities were in servicing lab equipment, building wiring harnesses, and testing battery pack voltages. On the side, I found an opportunity to build an application for streamlining an error reporting process. Though this project was a fraction of the overall internship experience, it most strongly contributed towards the “aspiring software engineer” narrative, and became my main point of discussion in resume and interviews.

Exclusion. This strategy is useful when there’s more than enough data points. Here, it’s better to trim off events that otherwise would’ve been adapted, because too many events ultimately get in the way of delivering the strongest, clearest narrative. With the above example, once I got more experience in software engineering, I could remove the data points on servicing equipment. They demonstrated that I could complete the tasks given to me, and future data points did the same thing and were more relevant.

Once we have the optimal set of included and adapted data points, we can shape our final delivery. The audience probably did not have the opportunity to experience the events conveyed - as in our interviewers didn’t watch us work our past jobs. Thus, the entire series of events is conveyed through our delivery. If our delivery is negative, then the audience’s perception is most likely negative. The outlook of the narrative is combined with the interviewer’s perception of the reliability of the narrator to form their own, final narrative on how great we are for the job.

Proactive Storytelling

A narrative can be formed from any past. It is beneficial to have a general idea of where we want to go before and during the work that is supposed to get us there. Our present experiences are very much like being in the middle of writing a novel. The more of an idea of the major plot points we want to reach, the easier time we’ll have applying our current situation to that.

In truth, we probably don’t know our own career end games. Thus, television sitcoms could be a more applicable analogy. In The Office, the show writers probably knew that Jim ends up with Pam in the end, but how they got there was shaped by practical realities, such as cast availability and season-by-season demand. In my freshman year, I had a test engineering job in front of me, and a software engineering plot point to work towards. Writing our “season” of a job experience involves thinking ahead to what our next couple seasons could look like.

Narrative Everything

Once we start looking for narratives, we can find them everywhere. A police investigation and the subsequent prosecution is a narrative. It attempts to recreate the series of events to maximize the guilty defendant narrative. A Hinge dating profile linearly arranges a series of achievements, travel experiences, and aspirations, providing the SparkNotes of our potential date. Nobel Prize winning economist Robert Shiller has taken this idea to the highest level, and made his latest professional fame on Narrative Economics - how narratives and information virality drive the direction of the economy. Storytelling is fundamental to the world that we live in, and our careers are no different.