Card Strength and Reputation: Face-work in the Home Poker Game

05 April 2016

On nights where there isn’t too much homework to be done or other social obligations to attend, a collection of familiar faces appear in a small Ann Arbor living room. These young college students sit on two opposing sofas—huddled over the coffee table, clacking away at their chips, shuffling cards, and having lively discussions about whatever comes to mind.

Ao, John, and Neeral sit around a makeshift home poker table.

Ao, John, and Neeral sit around a makeshift home poker table.

The main activity for the night is Texas Hold ‘em, which is the most popular variant of poker card games. I am somewhat of a regular at these home poker games, but this time I didn’t participate. Rather, I observed and recorded how hands were played, what was being said at the table, and how player attitudes changed as the game progressed. The game consists of an undefined number of “hands” (rounds) of play. In each hand, players are dealt two cards. There are three successive stages in each hand that involve revealing some of the remaining cards to the whole group, followed by betting [1]. Players match their own cards with ones on the table, hoping that future cards will secure them the best possible combination. Between these reveals are rounds where players bet on their hand in relation to the board. After the river [1], the players left in the hand reveal their cards, and the one with the best combination [2] takes the “pot,” or all of the money that was bet during the hand.

Poker at its core involves observing what hands others are representing, determining what they actually have, comparing that to your own hand in order to calculate the odds of winning, and making bets based on those odds. Reading others is fundamental to the game. Therefore, Goffman’s theory of self-presentation: that every individual in an interaction has a “face,” which is a self-determined identity taken for the purposes of the encounter, and that face is reinforced with actions or behaviors known as “lines,” will be heavily used in my argument (Goffman 1955:185). Furthermore, since a poker “game” on a macro-level consists of a continual series of these hands, the importance of groups, or self-identifiable divides among people based on their relations (Jenkins 1996:82), grows with the game.

In this macro level, we see the uniqueness of poker and the role of face-work. Goffman primarily focused on cooperation in face-work, in that groups will work out an interaction that mostly everyone is satisfied with (Goffman 1955). Even Jooyoung Lee’s work with rap ciphers focused on an interaction whose ultimate goal was to collaborate and preserve the group performance (Lee 2009). Poker is unique that there is no group collaboration in the face-work. Instead of building the interaction up, everyone is attempting to tear the others faces down, in order to win more money. In this essay, I will demonstrate that Goffman’s face-work is a fundamental driver in the game of poker both at the micro level, with actions taken during the hand as lines, and at the macro-level, where the role of what wealth group you are in and the faces you have put up throughout the game determine how others will play against you. The competitive nature of the game suggests that although the fundamental terms of “normal” social interactions and competitive social interactions are the same, the core lack of cooperation in a competitive environment like poker leads to a different corrective process for losing face.

At every round of betting, a player has choices to make. Each choice represents a line in the face they decide to take for their cards in the hand. “Folding” is to stop participating in the rest of the hand. This line gives the very blatant face that the player’s hand isn’t good enough to compete with the rest of the players. “Calling” is to match a previous players bet, but nothing more, which demonstrates medium confidence in the hand; perhaps a middle pair on board or a flush or straight draw [2]. “Raising” is to see that a previous player bet and to double that bet, forcing everyone else to either match with a call or fold and lose everything they have already put in. It is important to stress that besides folding, each face put on during a hand is the player’s own representation of the strength of their hand to the rest of the table, not necessarily the actual strength of their hand. In order to determine the validity of what I will call the card-strength-faces represented, players pull from past experiences and how the game has progressed thus far. This will be covered later in the essay.

An example of these basic mechanics in action is as follows. Arthur, a very calculating player, raises preflop [1], demonstrating a strong hand. His bet elicits groans from around the table. Three players fold, but Ao, a very aggressive player, calls. Ao is willing to pay the call amount to see if he will hit on the flop [1]. The flop comes, and Arthur bets an even larger amount. Arthur’s continuation bet follows Goffman’s idea of maintaining face, that the “line he effectively takes presents an image of him that is internally consistent… and that is confirmed by evidence conveyed through impersonal agencies in the situation” (Goffman 1955:186). Arthur’s consistent face of a strong hand forces the two remaining players in the hand to fold, allowing him to win the hand. A look at Arthur’s hand after the hand revealed that he had pocket aces, the best starting hand in the game.

Sometimes, maintaining a face can lead to a disastrous outcome. Goffman explains that people may “experience an immediate emotional response to the face… his feelings become attached to it” (Goffman 1955:185). Much like how some will develop a loyalty to their car brand or the timeshares they bought, players will get emotionally attached to their card-strength-face because they have already invested money into it. The worst case of attachment comes in the form of the “triple-barrel bluff,” demonstrated as such: Ao doesn’t have a very good hand, but bets pre-flop, trying to bluff and represent a strong hand. Tien, another calculating player, calls him. The flop shows up with an ace and a queen, which is very bad for Ao the bluffer, as actually good hands will have likely hit. Ao decides to bet anyways, hoping to get away with his lie, and Tien calls. This continues for the remaining rounds of the hand, with Ao pushing more and more money and Tien matching him. Ultimately, Tien reveals that he mostly knew he had Ao beat from the beginning, with an ace and a queen in his hand.

In theory, a game of poker could consist solely of the players gathering around the table, playing one hand, and then leaving, never to see each other again. In practice, very few people actually do that. We therefore observe that throughout the course of multiple hands, the whole night, and even between multiple games, players develop a face for what type of player they are and how good they are. In the long run, each individual hand played is a line in a type of face I will define as the meta-face. The ability to read the meta-face is just as important, if not more so, than the card-strength-face concepts discussed earlier. It is in this field that factors external to how the cards are represented come into play and things get truly interesting.

The most immediately apparent aspect of meta-face comes from the wealth gap that develops over the course of the game. To understand how this wealth gap affects the players, we turn to Jenkins’ idea of groups and categories. A group is a self-identifiable collective that is determined by the individuals, and a category is a “class whose nature and composition is decided by the person who defines the category” (Jenkins 1996: 82). In our case, the categories are the “short stacks,” who have much less chips compared to the rest of the table, and the “deep stacks,” who have many more chips. Since players can self-identify what they are based on how large their stack is in relation to the other players, they form groups of members with similar stack sizes. Being a small stack can get extremely frustrating to the individual and lead to “tilt,” playing non-optimally because of emotions. When Corey, who is generally known as a bad player (but a nice guy) became the small stack in the second hand of the game, he became tilted, stating that he’s “always unlucky in this game. [he] never gets good cards!” Later in the game. Neeral, who’s been slowly losing chips and has descended into the short stack category, vents: “I’ve been short stack this whole game! Look at all these large stacks around us!” to which Arthur replies: “I’m not huge! Ao is milking me too!” The short stacks at the table bond over their disadvantage, because having a deep stack truly has its privileges. A deep stack can raise pre-flop [1] with marginal hands [2], and shorter stacks will not have the wealth to take the risk and call. Deep stacks can effectively “bully” the shorter stacks in this sense. In the very next hand, Neeral wins big against Arthur, and Ao humorously notes that “the short stack bitcher is bigger than you.” Arthur replies that he’s now the short stack, and Neeral laughs and says bye to Arthur as he joins the normal sized stack group.

Belonging to a group at any certain time doesn’t necessarily deem you a “good” or “bad” player. Rather, it is simply one of the many lines that build into your meta-face. Ao became short stack early in the game, but Arthur turned to him and said “it’s okay Ao. You can give me all of you chips now and go on a rampage later [when he rebuys]!” [3] Clearly, there is still respect for Ao’s poker playing ability as he has a meta-face of an aggressive player that usually ends up winning big. On the other hand, even when Corey has deep stacks, he still is not taken seriously, and by the end of the night usually loses it all. When Ao bet small on a very one-dimensional straight board, everyone folded, even though Ao probably didn’t have it. To have the meta-face of a good player is important not only because of individual pride, but also because it inspires genuine respect and fear, which leads to advantages in game. This is probably why Ao thought he could get away with the triple-barrel bluffing discussed earlier in the essay.

Maintaining a meta-face is a very important aspect to success in poker. Therefore, there exists a corrective process for players when they lose their meta-face. Goffman defines The Corrective Process in face-work as “when the participants in an undertaking or encounter fail to prevent the occurrence of an event that is expressively incompatible with the judgments of social worth that are being maintained… [they] ratify it as a threat that deserves direct official attention – and [proceed] to try to correct for its effects” (Goffman 1955:190). In a given hand, there is one winner, and there are losers. The winner is the perpetrator and the losers are the ones hurt by the perpetrator. Unlike Goffman’s social interaction examples where the perpetrator corrects for the ones he/she has hurt (Goffman 1955: 191), the competitive nature of poker means that it is actually the ones hurt by the hand that are challenged by the group, not the perpetrator. The perpetrator’s meta-face is boosted from winning the hand, and the losers must find a way to prevent themselves from losing face. The actual rituals of the corrective process remain fairly standard.

When Arthur loses to Ao in a hand, he proclaims that “now [he] knows who to value bet.” This is a prime example of self-expiation, or as Goffman puts it, self-castigation, where the challenged acknowledges his wrongdoing and vows to not do it again. Basically, Arthur did not expect Ao to play a certain way and lost, but has told the table he knows why he lost and next time would not let Ao get away with it. Another common corrective process is to tell the dealer after they folded to “play it out” and deal the remaining cards onto the table, in order to justify their fold; even though it makes no difference what the future cards would have been after they fold. This is done as a compensation to themselves. After they fold and give up the hand and the pot, they want visual proof that they made the correct call. If those “played out” cards show that they could have won, even if they made the statistically correct call to fold, the player will generally be upset and vow to correct their play in the future to win these improbable hands. This corrective process is not a very good one, as it usually ends up putting the player on tilt.

I am not saying that the normal rules of social interaction are not present at the poker table. Many of the players have been friends for a long time, and have succeeded in doing so because of the processes Goffman describes. Rather, I claim that poker has its own independent application of face-work concepts as a core part of playing the game, both at the level of individual hands played, which I term the card-strength-face, and the wider reputation throughout multiple hands and games of poker, or the meta-face. Although I do claim poker face-work to be separate from social face-work, the two almost certainly do intersect at the home poker table, so a future exploration of that intersection may lend deeper insight into the subject.

Footnotes

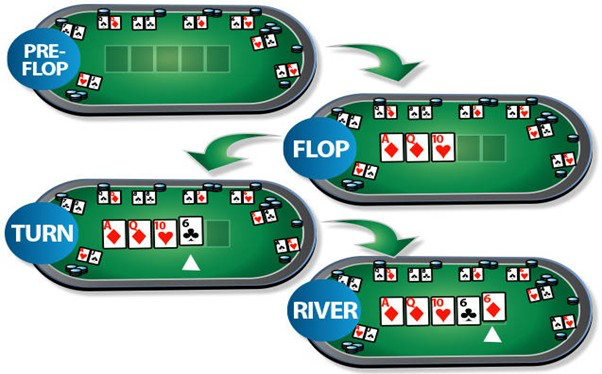

[1] Rounds in a hand of poker consist of four rounds of betting.

- Pre-flop: Each player has their own two cards only

- Flop: Three common cards are revealed.

- Turn: One card is revealed.

- River: One card is revealed.

Source: Hortense Shelton, slideplayer.com

Source: Hortense Shelton, slideplayer.com

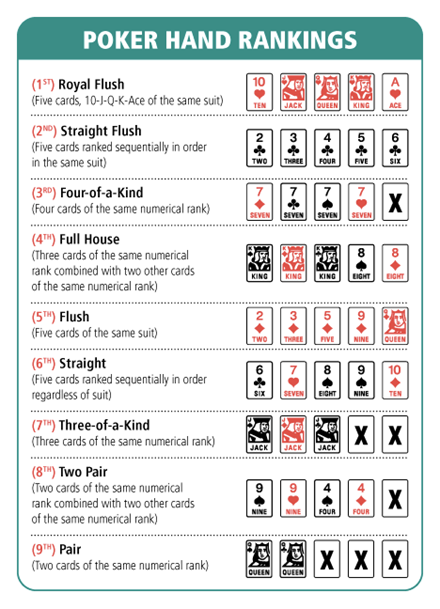

[2] Poker hand strengths chart. With your two cards and the cards on the table, you attempt to make the best possible combination.

Source: Lucas, strategy.minnim.org

Source: Lucas, strategy.minnim.org

[3] A rebuy is when you run out of chips, and have to “buy” more with money to continue participating in the game.

Citations

Goffman, Erving. 2012 [1955]. “On Face Work.” Pp. 185-195 in Readings for Sociology, 7th ed., edited by Garth Massey. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. Lee, Jooyoung. 2009.

“Escaping Embarrassment: Face-work in the Rap Cipher.” Social Psychology Quarterly 72(4):306-324.

Jenkins, Richard. 1996. Pp. 1-6 and 80-89 in Social Identity. London and New York: Routledge.